Basilica Cistern: A Subterranean Marvel

It was around 500 years ago when Petrus Gyllius, a French scholar visiting Istanbul heard strange stories of people drawing up water from holes in their cellars and some even found fish in that water! As he took an interest in these legends and the underground temples of the city, he decided to explore. It was not long before he discovered a huge cistern that was one of the remnants of the Byzantine Empire: the Basilica Cistern dating back to 532 AD.

Cisterns are stone-made cellars to stock up the waters of rain, lakes and rivers to be used when required. Before the Ottoman Empire set up its own water system, Byzantine cisterns generously provided the water needs of the people during periods of drought. They even worked as shelters after they were drained.

Cisterns are stone-made cellars to stock up the waters of rain, lakes and rivers to be used when required. Before the Ottoman Empire set up its own water system, Byzantine cisterns generously provided the water needs of the people during periods of drought. They even worked as shelters after they were drained.

Basilica Cistern is an underground cistern built by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great in Constantinople in order to store fresh water for the palace and nearby buildings. Nicknamed "The Sunken Palace" in Turkish, it is known in English as the "Basilica Cistern" because of its location on the site of the ancient Stoa Basilica, which doesn’t exist anymore.

Basilica Cistern is an underground cistern built by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian the Great in Constantinople in order to store fresh water for the palace and nearby buildings. Nicknamed "The Sunken Palace" in Turkish, it is known in English as the "Basilica Cistern" because of its location on the site of the ancient Stoa Basilica, which doesn’t exist anymore.

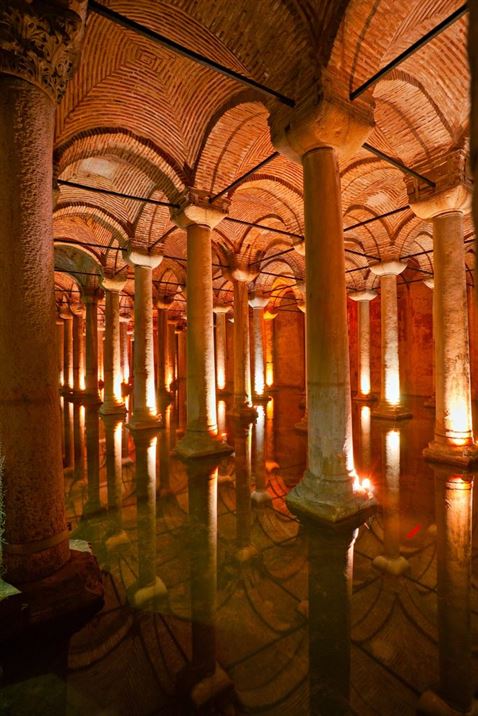

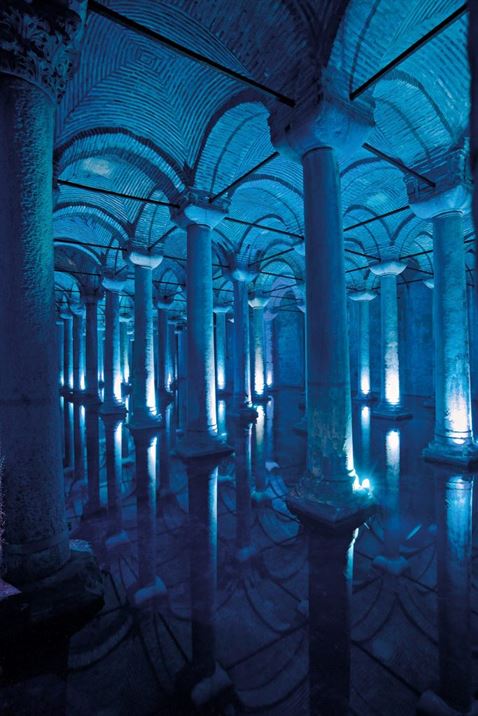

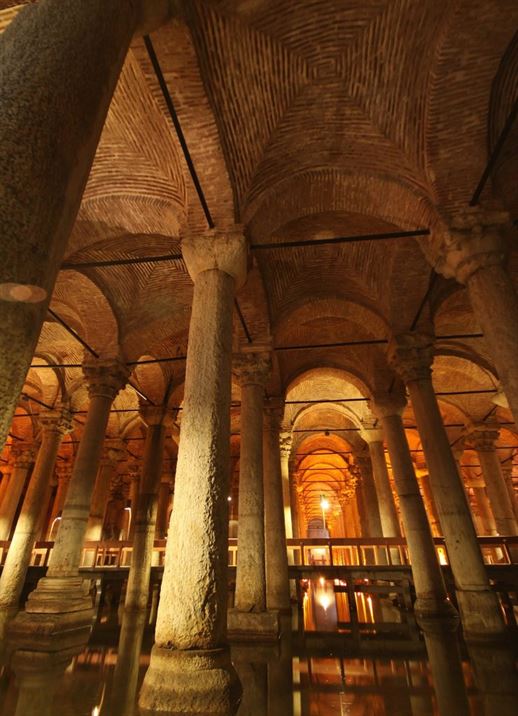

The size of two football fields, the cistern is roughly 140 meters long and 70 meters wide. This cistern is capable of holding up to 80,000 cubic metres of water. 336 marble columns supporting the structure, each measuring 9m in height, and arranged in 12 rows of 28 columns each divided by a distance of 4.9m. The majority of these columns were recycled from older buildings (a process known as ‘spoliation’), possibly brought to Constantinople from the various parts of the Byzantine Empire, as well as those used for the construction of the Hagia Sophia. One column differs from others with its engraved pictures resembling eyes and tears. As ancient texts suggest, these tears pay tribute to the hundreds of slaves who died during the construction of the cistern.

The size of two football fields, the cistern is roughly 140 meters long and 70 meters wide. This cistern is capable of holding up to 80,000 cubic metres of water. 336 marble columns supporting the structure, each measuring 9m in height, and arranged in 12 rows of 28 columns each divided by a distance of 4.9m. The majority of these columns were recycled from older buildings (a process known as ‘spoliation’), possibly brought to Constantinople from the various parts of the Byzantine Empire, as well as those used for the construction of the Hagia Sophia. One column differs from others with its engraved pictures resembling eyes and tears. As ancient texts suggest, these tears pay tribute to the hundreds of slaves who died during the construction of the cistern.

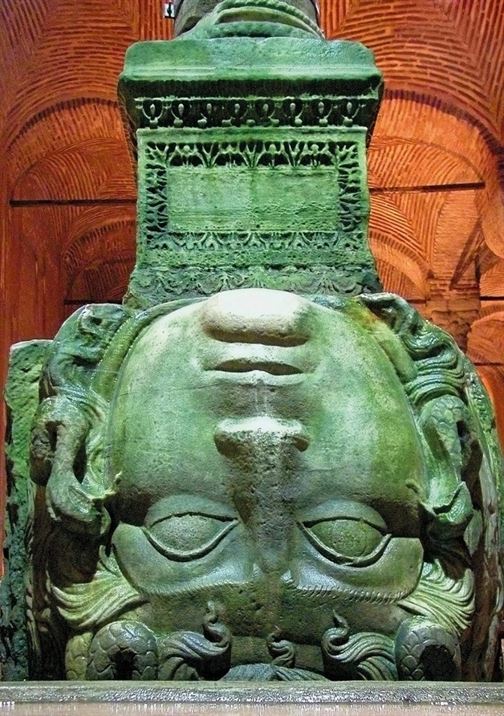

One of the most remarkable details of the cistern are the two giant pillar bases of two columns located in the corner, that are thought to be representing Medusa. According to legend, the heads were oriented sideways and upside down to counter the power of Medusa’s deadly gaze, though it is more likely these heads provided the proper sizes to support the columns.

One of the most remarkable details of the cistern are the two giant pillar bases of two columns located in the corner, that are thought to be representing Medusa. According to legend, the heads were oriented sideways and upside down to counter the power of Medusa’s deadly gaze, though it is more likely these heads provided the proper sizes to support the columns.

Even though the subterranean cistern was not a centre of attraction throughout its history, it was well preserved and restored several times after the re-discovery of Petrus Gyllius. The most recent restoration was in the late 1980s, when lighting, elevated walkways, and a café were added for the convenience of visitors. Even though the cistern holds only a small amount of water today, fish can still be found in it in order to keep the water clear.

Even though the subterranean cistern was not a centre of attraction throughout its history, it was well preserved and restored several times after the re-discovery of Petrus Gyllius. The most recent restoration was in the late 1980s, when lighting, elevated walkways, and a café were added for the convenience of visitors. Even though the cistern holds only a small amount of water today, fish can still be found in it in order to keep the water clear.

Comments